Farewell to India- for now.

I write this on my last night in India.

Seven weeks in India. Seven weeks of what?

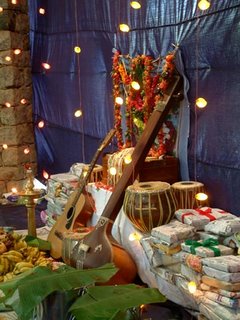

Of colour, lots of it. Colour as iridescent saris blaze around every street corner. Then the glossy black and yellow of taxis and the glaring orange of festival flowers. The piquant green of tea plantations. The lush green of coconut plantations. The lazy green of cardamom trees. The black of a girl’s oiled hair, the black of men’s moustaches, the pupils of eyes (you staring at them, them staring at you). The chorus of colour as Diwali swings into fare; fireworks painting the sky like a circus. The pink of pickle. The night blue of night trains. The bright light of bright days.

Seven weeks of bright, busy days.

Looking back on my time here, I realise I’ve been to places and done things I never thought I would do.

Travelling at speed on the back of motorbikes through the alleyways of Mumbai, and Chennai, and other unpronounable places like Thiruvananthapuram. Wild rickshaw rides. Slow taxi rides. Plenty of traffic jams. Wonderful, long, lulling train journeys. Queues. More queues. Waits. Punctures. Blessings. Grace.

I’ve been to a school experimenting with science teaching. Another with children’s banking. Another with philosophy. I’ve visited women ragpickers who have joined together to form recycling units. I’ve been to a bio-gas plant. I’ve had a jiving lesson. I’ve sat in on karate classes. I’ve been to a surprise party. I’ve had conversations about venture philanthropy, partnership, business, arranged marriage, female infanticide, terrorism, corruption, altruism, God, schizophrenia, innovations, marketing strategy, Bollywood, home, love. I’ve lost count of the cups of chai I’ve drunk.

I’ve swum in the Arabian Sea. Paddled in the Indian Ocean. I’ve gone on long walks, got lost, and ended up on longer walks. I’ve been to a Jatropha plantation. I’ve sat with professors, teachers, scientists, social workers, politicians, restaurateurs. I’ve learned about the long-term commitment needed for rural transformation. I’ve learned about artificial insemination in cows. I’ve been to a mushroom farm, a bio-technology lab, a vocational college.

I’ve been into temples. I’ve been blessed with blessed water. I’ve been given flowers, sweets, spontaneous hugs. I’ve meditated in Auroville’s matrimandir. I’ve seen a solar powered kitchen and a battery powered car. I’ve met people working to combat child sex abuse, child labour, child trafficking. I’ve met others working to promote rural innovation. I’ve met a women who creates beautiful children’s literature. I’ve met another who helps kick-start social ventures. I’ve met up with old friends from Ireland and met lots of new friends.

I’ve seen flowers which bloom once every twelve years. I’ve seen ancient sculpture. I’ve been to a crocodile farm. I’ve touched a python. I’ve seen women stand up for their rights. I’ve danced with former child labourers and heard the stories of their liberation, from their liberators. I’ve given puppet shows, with mixed success.

I’ve given to beggars. Stepped over beggars. Not known how to respond to beggars.

I’ve lost my wallet (again), and had it returned to me, money and cards intact (again).

I’ve been to an adoption centre. I’ve been to tiny roadside restaurants and five star hotels. I’ve been into the homes of people celebrating their sacred festivals.

I’ve laughed. I’ve cried. I’ve been exhausted. I’ve been exhilarated. I’ve been learning. I’ve been trying to make sense of it all.

Travel does this to you. It enriches as it shakes. Perceptions start to shift and alter. You start to shift and alter. You take a step and the world unfolds with colour and learning. You take a step and the world takes the next ten.

The world? Well, it’s the people you meet along the way who point you in the right direction. Or a book you read which clarifies a point. Or a film you see which sparks a train of new thought. Or that kid you play football with. Or that mother you make eye contact with. Or that beggar you pass on the street.

Seven weeks. I know. I can hardly believe how much can be packed in. A lot has happened, and there is still a lot more to come.

I am thankful. I am lucky. I am learning.

The journey continues. Onwards. Inwards. Outwards.